Sleep is a universal human need, as essential as nutrition and physical activity. Yet, sleep disorders are common, underdiagnosed, and often poorly managed. Globally, it is estimated that up to 45% of the population experience at least one sleep-related problem during their lifetime. In Ireland, as in many other countries, surveys suggest that around one in three adults regularly suffers from poor sleep. This has profound implications—not only for individuals’ health and wellbeing, but also for the healthcare system, workplace productivity, and society as a whole.

Pharmacists occupy a unique position in tackling sleep disorders. As one of the most accessible healthcare professionals, pharmacists are often the first point of contact for patients reporting sleep difficulties. They are trusted to provide advice, triage, and safe supply of medicines. Moreover, their expanding role in medication reviews, deprescribing initiatives, and primary care collaboration means pharmacists increasingly contribute to sleep health management across settings.

This CPD article provides an up-to-date overview of common sleep disorders, with a focus on equipping pharmacists to:

• Identify and differentiate between sleep conditions.

• Support patients with non-pharmacological and pharmacological management.

• Recognise red flags requiring referral.

• Reflect on their professional responsibilities in safe supply, deprescribing, and monitoring.

60 Second Summary

Sleep is a universal human need, as essential as nutrition and physical activity. Yet, sleep disorders are common, underdiagnosed, and often poorly managed. Globally, it is estimated that up to 45% of the population experience at least one sleep-related problem during their lifetime. In Ireland, as in many other countries, surveys suggest that around one in three adults regularly suffers from poor sleep. This has profound implications—not only for individuals’ health and wellbeing, but also for the healthcare system, workplace productivity, and society as a whole.

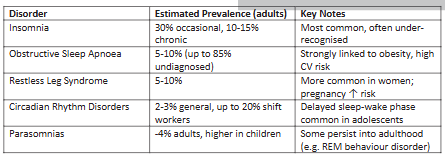

Sleep disorders are remarkably common across the population, with epidemiological studies consistently showing that they affect a substantial proportion of both adults and children. Among these, insomnia stands out as the most prevalent condition. Surveys indicate that around 30% of adults experience occasional episodes of insomnia, while between 10–15% meet the criteria for chronic insomnia, defined as sleep difficulties occurring at least three nights per week for three months or longer.

Beyond the direct burden on individuals, sleep disorders collectively impose a considerable economic cost.

Although precise Irish data are limited, international research indicates that insufficient sleep costs economies billions of euro annually through lost productivity, workplace absenteeism, accidents, and increased healthcare utilisation.

The development of sleep disorders is rarely attributable to a single cause; rather, it results from a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Demographic characteristics play an important role, with sleep problems more frequently reported in older adults, women, and during key life stages such as pregnancy and menopause.

Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Impact of Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders are remarkably common across the population, with epidemiological studies consistently showing that they affect a substantial proportion of both adults and children. Among these, insomnia stands out as the most prevalent condition. Surveys indicate that around 30% of adults experience occasional episodes of insomnia, while between 10–15% meet the criteria for chronic insomnia, defined as sleep difficulties occurring at least three nights per week for three months or longer. Insomnia is often under-reported and undertreated, with many individuals normalising their symptoms or attributing them to stress, ageing, or lifestyle pressures. The condition is not only distressing in itself but also strongly associated with the development of anxiety, depression, and long-term health complications such as cardiovascular disease and metabolic dysfunction.

Another significant contributor to the sleep health burden is obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). It is estimated to affect between 5–10% of adults, though the true prevalence is likely much higher, as up to 85% of cases remain undiagnosed. OSA occurs when the upper airway repeatedly collapses during sleep, leading to fragmented rest and intermittent hypoxia. The prevalence of OSA is rising in parallel with the obesity epidemic, and it is strongly associated with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular morbidity. Left untreated, it not only impairs quality of life but also significantly increases the risk of road traffic accidents due to excessive daytime sleepiness.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is another relatively common condition, affecting 5–10% of adults, with symptoms typically becoming more pronounced with advancing age. Women are disproportionately affected, and prevalence is particularly high during pregnancy. The syndrome is characterised by an uncomfortable urge to move the legs, often leading to difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep. While many patients experience mild, intermittent symptoms, severe RLS can be profoundly disabling and may be linked to iron deficiency, renal disease, or neuropathy.

Circadian rhythm disorders represent a different category of sleep disturbance, in which the timing of the body’s internal clock is misaligned with environmental or social demands. These disorders are relatively uncommon in the general population, affecting around 2–3%, but are particularly prevalent in specific groups such as shift workers. Among this population, studies suggest that up to 20% may develop clinically significant shift work sleep disorder, characterised by insomnia, excessive sleepiness, and impaired daytime functioning. Adolescents and young adults are also especially vulnerable to delayed sleep–wake phase disorder, where difficulty falling asleep until the early hours leads to chronic sleep deprivation when social or occupational schedules require early rising.

Parasomnias, such as sleepwalking, night terrors, and REM sleep behaviour disorder, are less common overall, with a prevalence of around 4% in adults. However, they are much more frequent in childhood, where they can cause considerable distress to both children and their families. While many parasomnias are self-limiting and benign, some can persist into adulthood or present risks of injury to the patient or others. In the case of REM sleep behaviour disorder, prevalence increases with age and may act as an early marker of neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease.

Risk factors

The development of sleep disorders is rarely attributable to a single cause; rather, it results from a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Demographic characteristics play an important role, with sleep problems more frequently reported in older adults, women, and during key life stages such as pregnancy and menopause. Ageing is associated with changes in circadian rhythm, reduced slow-wave sleep, and increased prevalence of chronic illness, all of which contribute to fragmented rest.

Medical comorbidities are another significant risk factor. Conditions

Table 1: Prevalence of Common Sleep Disorders

such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disorders, depression, and anxiety are strongly associated with poor sleep. Painful musculoskeletal conditions and neurological diseases, including Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, also contribute to disordered sleep by disrupting both the initiation and maintenance of sleep. Importantly, the relationship between sleep disorders and medical conditions is bidirectional: for example, insomnia increases the risk of depression, while depression itself is a common cause of insomnia.

Medications may also directly impact sleep quality. Stimulant drugs, including corticosteroids, decongestants, and certain antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), can lead to insomnia. Beta-blockers are known to suppress melatonin secretion and cause vivid dreams or nightmares. Conversely, sedative medicines used inappropriately can trigger rebound insomnia upon withdrawal. Pharmacists must therefore remain vigilant when conducting medication reviews to identify iatrogenic contributors to sleep problems.

Lifestyle factors also play an important role. High caffeine intake, excessive alcohol use, nicotine dependence, and late-night use of electronic devices all contribute to poor sleep. Modern societal trends, including 24-hour working patterns and increased screen exposure, create environments that make sleep disruption more likely. Environmental conditions such as noise, light, and poor housing quality can also undermine sleep. Occupational demands— particularly shift work—are strongly linked to circadian rhythm disorders and chronic sleep deprivation.

Finally, genetic and familial influences cannot be overlooked. Studies suggest a heritable component to conditions such as restless legs syndrome and narcolepsy, while insomnia often runs in families, potentially due to a mixture of genetic predisposition and shared behaviours.

Health Impact

• Physical health: Poor sleep is a recognised risk factor for obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, impaired glucose metabolism, and reduced immunity.

• Mental health: Strongly linked to depression and anxiety; poor sleep is both a cause and a consequence.

Differentiating Common Sleep Disorders

• Safety: Sleep deprivation contributes to road traffic accidents and occupational hazards.

• Quality of life: Daytime fatigue, irritability, reduced productivity, and impaired relationships.

Beyond the direct burden on individuals, sleep disorders collectively impose a considerable economic cost. Although precise Irish data are limited, international research indicates that insufficient sleep costs economies billions of euro annually through lost productivity, workplace absenteeism, accidents, and increased healthcare utilisation. Given the comparable prevalence of sleep disorders in Ireland, it is reasonable to expect a similar burden here. The societal impact is amplified by the strong association between sleep disorders and chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, and dementia. Furthermore, the risks to safety are significant, with sleeprelated impairment contributing to road traffic collisions and occupational injuries.

Differentiating Common Sleep Disorders

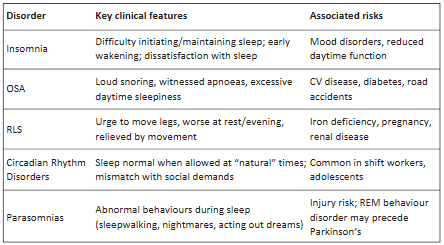

In practice, pharmacists may encounter patients presenting with non-specific complaints such as tiredness, difficulty sleeping, or daytime fatigue. The ability to distinguish between different types of sleep disorders is therefore critical for effective advice and referral.

Insomnia remains the most commonly reported disorder. Patients typically describe difficulty falling asleep, waking frequently during the night, or rising earlier than intended, often accompanied by feelings of irritability, poor concentration, and fatigue during the day. Insomnia can be short-term, triggered by stress, bereavement, or illness, or chronic, lasting for months or years. Unlike other conditions, the hallmark of insomnia is a persistent dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality despite adequate opportunity for rest.

In contrast, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is characterised by loud snoring, nocturnal choking or gasping, and witnessed pauses in breathing during sleep. Patients may complain less about difficulty sleeping and more about feeling excessively sleepy during the day, often falling asleep unintentionally at work, while reading, or even when driving. OSA is strongly associated with obesity and carries significant risks for cardiovascular health, making prompt recognition and referral essential.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) presents differently. Patients usually describe an uncomfortable or tingling sensation in the legs, accompanied by an overwhelming urge to move. Symptoms are typically worse in the evening or at rest and may be temporarily relieved by walking or stretching. RLS can severely delay sleep onset and cause frequent awakenings, leading to secondary insomnia. Its association with iron deficiency, pregnancy, and chronic kidney disease is an important clue to underlying causes.

Circadian rhythm disorders represent a misalignment between the body’s internal clock and external social or occupational demands. In delayed sleep–wake phase disorder, commonly seen in adolescents and young adults, patients find it difficult to fall asleep before the early hours, which results in insufficient sleep during the week. Shift workers are vulnerable to irregular sleep patterns, with up to one in five developing clinical symptoms of insomnia and excessive sleepiness. Unlike insomnia, the sleep itself is of normal quality and duration when permitted to occur at the “right” time.

Parasomnias are distinct in that they involve abnormal behaviours or experiences during sleep. Non-REM parasomnias include sleepwalking and night terrors, typically arising in childhood but sometimes persisting into adulthood. REM parasomnias include vivid nightmares and REM sleep behaviour disorder, where patients physically act out dreams, sometimes violently. These disorders can cause injury to the patient or bed partner and may signal underlying neurological disease.

To support differentiation, pharmacists may find validated tools useful. The Insomnia Severity Index can help measure sleep disturbance, while the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and STOP-BANG questionnaire are widely used to assess risk of OSA. Asking structured questions about symptom onset, duration, pattern, and associated features provides critical clues to the underlying disorder.

Non-pharmacological management

Non-drug strategies are considered first-line in nearly all sleep disorders, and pharmacists can play a pivotal role in reinforcing these approaches. Sleep hygiene advice is the foundation of good sleep health. Patients should be encouraged to establish regular sleep and wake times, even on weekends, and to create a relaxing pre-bedtime routine. Reducing stimulants such as caffeine and nicotine, limiting alcohol in the evening, and ensuring that bedrooms are cool, quiet, and dark are simple but effective steps. Avoiding electronic screens before bed is particularly important, as blue light exposure can suppress melatonin secretion and delay sleep onset.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is considered the gold standard for managing chronic insomnia. Unlike pharmacological treatments, CBT-I addresses the behavioural and cognitive factors perpetuating poor sleep. Techniques include stimulus control, which strengthens the association between bed and sleep by limiting time spent awake in bed, and sleep restriction, which initially reduces time in bed to consolidate sleep before gradually increasing it. Cognitive restructuring helps patients challenge unhelpful beliefs about sleep, such as the idea that one must achieve a fixed number of hours to function. Relaxation training, mindfulness, and breathing exercises are often incorporated. Evidence shows that CBT-I produces durable improvements that often outlast medication-based therapies. With the growing availability of digital CBT-I platforms, pharmacists can signpost patients to accessible, evidence-based resources, some of which are NHS-approved.

Other behavioural approaches are equally important for specific disorders. In OSA, lifestyle measures such as weight loss, positional therapy, and reducing alcohol or sedative use are essential alongside medical treatment. For RLS, correcting iron deficiency can significantly reduce symptoms, while avoiding triggers such as caffeine, antihistamines, and prolonged inactivity can also help. Circadian rhythm disorders may benefit from carefully timed light exposure or melatonin supplementation to reset the body clock, while parasomnias can often be managed through reassurance, stress reduction, and environmental safety measures such as locking doors and removing hazards from bedrooms.

Practical tip

Pharmacists can use screening tools such as:

• Epworth Sleepiness Scale (for OSA).

• Insomnia Severity Index.

• STOP-BANG questionnaire (OSA risk).

Non-Pharmacological Management

Sleep hygiene

Pharmacists should deliver consistent advice:

• Maintain regular bed/wake times.

• Avoid caffeine, nicotine, alcohol late in the day.

• Reduce screen use before bed.

• Keep bedroom cool, quiet, and dark.

• Restrict bed use to sleep/sex only.

• Encourage physical activity, but not too close to bedtime.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

The gold standard for chronic insomnia.

• Stimulus control: Go to bed only when sleepy; leave bed if unable to sleep within 20 mins.

• Sleep restriction: Limit time in bed to actual sleep time, then gradually increase.

• Cognitive restructuring: Challenge negative beliefs (“I must get 8 hours”).

• Relaxation techniques: Progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness, breathing exercises.

• Delivery: Face-to-face, group.

Other behavioural approaches

• OSA: Weight loss, reduced alcohol/sedative use, positional therapy.

• RLS: Correct iron deficiency, avoid triggers (caffeine, antihistamines).

• Circadian disorders: Timed light exposure, melatonin.

• Parasomnias: Reassurance, safety measures, stress management.

Pharmacological Management

Although non-pharmacological approaches remain the mainstay of treatment, pharmacological therapies are sometimes necessary, particularly when symptoms are severe, persistent, or when behavioural interventions alone prove insufficient.

For insomnia, benzodiazepines such as temazepam and loprazolam are effective short-term hypnotics, working by enhancing GABA-A receptor activity to promote sleep. However, they are associated with tolerance, dependence, and cognitive impairment, particularly in older adults, and guidelines recommend restricting use to no longer than four weeks. Non-benzodiazepine “Z-drugs” such as zopiclone and zolpidem act similarly, but are often preferred due to a slightly more favourable side-effect profile. Nevertheless, they carry comparable risks of dependence and next-day sedation, as well as rare but serious parasomnias such as sleep-driving.

In Ireland, melatonin is available only on prescription and is not routinely reimbursed under the HSE Primary Care Reimbursement Service, except in certain specialist indications such as paediatric neurodevelopmental disorders. While melatonin has a relatively benign side-effect profile and may be useful in circadian rhythm disorders, its efficacy is modest and the timing of administration is crucial for optimal benefit. Sedating antidepressants, including trazodone and mirtazapine, are sometimes used off-label for insomnia, particularly in the presence of comorbid depression, although robust evidence for their effectiveness remains limited.

Over-the-counter sedating antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine and promethazine, are widely available in Ireland and may provide shortterm relief of sleep difficulties for some individuals.

In OSA, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) remains the gold standard, with pharmacological treatment limited to select cases. For example, modafinil, a wakepromoting agent, may be used in specialist settings for patients with residual daytime sleepiness despite optimal CPAP use.

For RLS, dopamine agonists such as ropinirole and pramipexole are effective but carry the risk of augmentation, where symptoms worsen and appear earlier in the day, as well as impulse control disorders. Alpha-2-delta ligands such as gabapentin and pregabalin are increasingly preferred, particularly in patients with comorbid pain or insomnia. Correction of iron deficiency is fundamental if ferritin levels are below 75 µg/L, as this can alleviate symptoms without the need for long-term medication.

Circadian rhythm disorders may be managed pharmacologically with melatonin, administered at carefully timed intervals to shift the sleep–wake cycle. In shift work disorder, stimulants or wake-promoting agents may sometimes be used under specialist guidance, though these are not first-line. Parasomnias rarely require medication, but severe cases of REM sleep behaviour disorder may respond to clonazepam or melatonin under specialist supervision.

Pharmacist-Led Advice, Support, and Referral

Pharmacists’ contribution includes:

• Education: Providing accurate, accessible advice on sleep hygiene and therapies.

• Early identification: Recognising red flags such as loud snoring/ apnoeas, severe daytime sleepiness, violent parasomnias.

• Safe supply: Ensuring hypnotics are used short term, with full counselling.

• Medication review: Identifying drugs contributing to insomnia (e.g., corticosteroids, SSRIs, stimulants).

• Referral:

o To GPs for diagnostic workup (sleep studies, iron studies, psychiatric assessment).

o To sleep clinics such as Beaumont Hospital, Tallaght University Hospital, Cork University Hospital or Galway University Hospital for suspected OSA.

o To HSE mental health services for comorbid anxiety/depression.

Professional Responsibilities

Pharmacists carry significant responsibility in ensuring that sleep medicines are prescribed, supplied, and monitored safely. Safe supply is critical, particularly given the risks of dependence and adverse effects associated with hypnotics. Pharmacists should ensure that these medicines are dispensed in line with local and national guidelines, accompanied by clear counselling on appropriate use, side effects, and risks such as driving impairment and interactions with alcohol or other central nervous system depressants.

A major part of the pharmacist’s role is in deprescribing. Longterm use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs remains common despite guidelines, especially among older adults. Pharmacists can identify such patients during medication reviews and work collaboratively with prescribers to support gradual withdrawal. Tapering regimens, often involving dose reductions of 10–25% every one to two weeks, can minimise withdrawal symptoms and improve success rates. Crucially, deprescribing must be combined with non-pharmacological support, reassurance, and monitoring.

Monitoring is another professional obligation. Patients taking sleep medicines should be regularly reviewed for efficacy, adverse effects, and ongoing need. Pharmacists should be alert to potential misuse or diversion and

use tools such as sleep diaries or digital apps to help patients track progress. They should also consider the impact of other medicines that may worsen sleep and recommend alternatives where appropriate.

Finally, there are ethical and professional considerations. Pharmacists must balance patient expectations—often for rapid, pharmacological solutions— with the longer-term benefits of behavioural interventions. Supporting vulnerable populations, including older adults and patients with mental health conditions, requires sensitivity and adherence to professional standards. Upholding PSI principles of patient-centred care, safety, and effective communication ensures that pharmacists provide the highest standard of support in managing sleep disorders.

CASE STUDIES

Case 1 Suspected OSA

A 52-year-old obese man reports constant fatigue and his partner notes loud snoring and pauses in breathing.

• Pharmacist’s role: Recognise red flag, refer promptly to GP/ sleep clinic, advise on weight reduction and avoiding alcohol.

Case 2: Restless legs syndrome

A 40-year-old woman reports tingling in her legs at night, making it difficult to sleep.

• Pharmacist’s role: Explore history, suggest iron studies via GP, advise on lifestyle measures, and discuss treatment options if confirmed.

Conclusion

Sleep disorders are highly prevalent, significantly impacting health, wellbeing, and healthcare costs. Pharmacists are ideally placed to support patients through early identification, patient education, safe supply of medicines, and referral where appropriate. Non-pharmacological interventions such as CBT-I remain first-line, with pharmacological treatments used cautiously and short-term.

Reflecting on professional responsibilities—including safe supply, deprescribing, and monitoring—ensures pharmacists practise safely and add value to multidisciplinary management of sleep disorders.

Written by Denis O’Driscoll, Superintendent Pharmacist, McCabes Pharmacy Group

Denis O’Driscoll has 26 years’ experience in pharmacy. After spending most of his career as an addiction expert, Denis moved to the role of Superintendent Pharmacist for the McCabe’s Pharmacy group (formerly Lloyds Pharmacy). He is responsible for the management and delivery of quality pharmacy services to the public.

Denis is also the voluntary independent chair of the Naloxone Advisory Group for the HSE Strategy on Overdose Prevention. Denis is a graduate of pharmacy from Trinity College Dublin and has a PhD in Biopharmaceutics (TCD).

Denis is a pharmacist appointee to the PSI Council and President of the PSI.

Catch more at IPN HERE

Read IPN October HERE