Dry eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial ocular surface disorder characterised by loss of tear film homoeostasis and may result in various ocular symptoms and visual disturbances.1 DED pathology can significantly affect an individual’s visual function, quality of life2 and work productivity3 and has been associated with lower health utility.4 Moreover, DED can have considerable negative personal and socioeconomic repercussions.5 This includes direct economic costs, such as medical professional visits and treatment costs and intangible personal costs, including impaired social, emotional and physical function.6

According to the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS), the global prevalence of DED ranges between 5% and 50% in the general population, and epidemiological studies vary widely in terms of geographical and age differences, and diagnostic criteria.7 It is currently agreed that the prevalence of DED is higher in people over 50 years of age, especially among postmenopausal women.8 The prevalence of DED may be higher in Asia than in other regions.9 It has been reported that lower DED prevalence is associated with higher latitude and relative humidity and a temperate climate.10

The prevalence and contributing mechanisms in DED among children are influenced by multiple factors related to congenital, autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, and the condition may also be caused or exacerbated by factors such as the living environment.11 With the popularisation of computers and smartphones, associated exposure to electronic screens that emit blue light and decreased blink rates have led to an increase in the prevalence of DED.12 Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, children around the world stayed at home and studied online, leading to an increase in complaints of dry eyes and visual fatigue.13 In addition, wearing face masks, a widespread public health intervention during the pandemic, is a risk factor for DED. Many children had difficulty finding a mask that fits well and was easy to wear correctly.14

The epidemiology and pathological processes of DED in children have not been described as comprehensively as in adults.15 Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and metaanalysis to understand the current profile associated with childhood DED. Accurate estimation of the current prevalence of paediatric DED is essential for developing

appropriate strategies to promote paediatric ocular surface health on a global scale.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist guidelines.16 Data extraction, risk of bias assessment and statistical analyses were conducted following the methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023343999) on 24 April 2023. Following the first review, we adjusted our analysis plan and updated the registration on 18 September 2024. Our revised inclusion criteria now focus on cross-sectional studies involving children under 18 years of age. We added an analysis of children wearing contact lenses, along with subgroup analyses based on study setting, DED diagnostic methods, climate zones and regions (Asian vs non-Asian). Additionally, we included a regression analysis of climate factors (temperature, latitude, humidity and rainfall) and prevalence. The final literature search was conducted on 1 April 2024.

Results

Study characteristics

The initial literature search identified 7309 articles. After removing 2911 duplicates, 4398 titles and abstracts were screened. After screening the titles and abstracts, 85 articles were retained and assessed for eligibility, among which 41 articles24–64 were included in the review (figure 1). One article investigated the situation in both the Philippines and South Korea, which we reported separately, resulting in a total of 42 studies for meta-analysis. Donthineni et al found only 1023 cases of DED (0.4%) in a retrospective study of 259 969 children from 2010 to 2018 using electronic medical records.65 The use of electronic records may reduce sensitivity, and more than 30% of the children were older than 18. Additionally, the study had a long observation period. Due to these limitations, it was excluded from the meta-analysis despite its large sample size.

All 42 studies included in the meta-analysis were cross-sectional and were conducted from 2008 to 2023. The studies included 48 479 participants (median 368; IQR 223–1926; range 60–5006) and were conducted in 14 countries, of which 35 studies (83.3%) were from Asia.24–46 50 51 54 55 57–59 61–64

Four studies (9.5%) were from lower-middle-income countries (1 each from India,41 Indonesia,42 Egypt60 and the Philippines64), 27 (62.3%) from upper-middle-income countries (1 each from Colombia48 Mexico53 and Thailand62) and 24 (58.5%) from China25–40 45 46 51 54 57–59 63) and 11 (26.2%) from highincome countries (1 each from New Zealand47, the UK49 and Saudi Arabia61; 2 from Japan24 50 and the USA,52 56 and 4 from South Korea34 43 44 55). 25 studies (59.5%) were conducted in a school or community setting,26 28–30 32 35 36 38 40 42–44 46 48–51 53 55 57 58 62–64 while the rest (n=17, 40.5%) in clinical settings.25 27 31 33 34 37 39 41 45 47 52 54 56 59-61

20 studies contained an approximately equal number of girls and boys,24 26 28–30 32 35 36 38–41 43 45 51 53 57–59 63 4 studies included <40% girls31 33 44 50 and 1 study included <40% boys.62 17 studies did not report on the gender distribution of participants.25 27 30 34 37 42 46–49 52 54–56 60 64 One study investigated the situation in both the Philippines and South Korea, which we reported separately.64

There was heterogeneity (p=0.01) among the four groups of studies formed by diagnostic criteria and setting. Lower values of DED prevalence were recorded in studies using clinical diagnosis as diagnostic criteria: 19.3% (95% CI 15.4% to 23.2%; I2=86.1%; 11 studies; 2849 children) in clinical setting and 14.7% (95% CI 10.9% to 18.6%; I2=98.8%; 15 studies; 24 258 children) in school/community setting. Studies using questionnaire to diagnose DED recorded higher prevalence estimates: 29.8% (95% CI 10.7% to 48.8%; I2=99.6%; 6 studies; 2329 children) in clinical setting and 37.5% (95% CI 23.8% to 51.3%; I2=99.8%; 9 studies; 19 043 children) in school/community

setting. Heterogeneity was high in all groups formed by diagnostic criteria and setting, as expected in observational prevalence studies. Among studies using symptoms for DED diagnosis, there was a larger spread of prevalence estimates, with four studies finding values above 60%.

Prevalence of DED: subgroup analyses

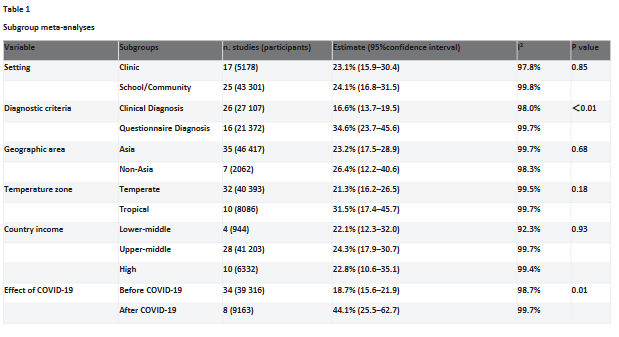

Table 1 shows the results of subgroup analyses by setting, diagnostic criteria, geographical area, temperature zone, country income and effect of COVID-19. In terms of setting subgroups, there are no statistically significant differences, the prevalence of school/community studies with

better representation of the population being 24.1% (95% CI 16.8% to 31.5%; I2= 99.8%; 25 studies; 43 301 children) and the prevalence of clinical studies being 23.1% (95% CI 15.9% to 30.4%; I2= 97.8%; 17 studies; 5178 children). Diagnostic criteria subgroups were statistically significantly different (p<0.01 for subgroup heterogeneity), with clinical diagnosis yielding nearly half the DED prevalence compared with questionnaire diagnosis: 16.6% (95% CI 13.7% to 19.5%; I2=98.0%; 26 studies; 27 107 children) and 34.6% (95% CI 23.7% to 45.6%; I2=99.7%; 16 studies; 21 372 children), respectively. Prevalence was statistically significantly different before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (subgroup heterogeneity p<0.01), where the prevalence of DED in studies before COVID-19 was 18.7% (95% CI 15.6% to 21.9%; I2=98.7%; 34 studies; 39 316 children) and after the start of the pandemic the prevalence of DED increased to 44.1% (95% CI 25.5% to 62.7%; I2=99.7%; 8 studies; 9163 children). Small differences in pooled estimates were apparent for other subgroups, but none were statistically significant.

Prevalence of DED: meta-regression on climate determinants

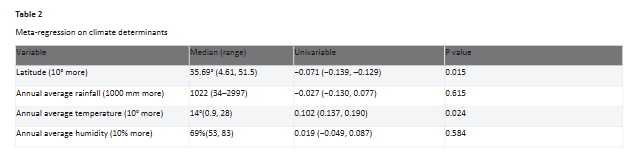

Table 2 shows the results of the meta-regression, including latitude (a proxy of temperature and sun irradiation), average annual rainfall, average annual temperature and average annual humidity for each study. In the univariable model, both latitude and average annual temperature were statistically significantly associated with DED, where DED prevalence increased by 7.1% for each 10° decrease in latitude (ie, moving towards the equator, p=0.015) and by 10.2% for each 10° mm increase in average annual temperate (p=0.010).

Discussion

While DED has been widely recognised as a common eye disease in adults, it has been understudied in children.15 The current study provides a comprehensive estimate of the global prevalence of DED in children and explores factors associated with DED. Our review identified no other studies

reporting separately on the global prevalence of DED among children. We also observed an apparent increase in DED among children after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most notably, this review found that DED diagnosis by clinical signs versus by questionnaires of symptoms in children yield very different prevalence figures and require further study.

Our results suggest that the prevalence of DED among children is close to that in the adult population. The current study estimated the overall prevalence of DED in children to be 23.7%. A number of previous systematic reviews have reported DED estimates globally, and for Africa, Asia and the USA. The estimated prevalence of DED in Africa is 42.0% (95% CI 30.7% to 53.8%).66

In relation to Asia, Cai et al included four studies reporting the prevalence of DED in people under 20 years old, and estimated that 11.9% of individuals suffer from DED (95% CI 4.4% to 19.4%).67 A study in the USA reported that the population prevalence of DED was 8.1% (95% CI 4.9% to 13.1%), lower than seen in our study.68 It is imperative to acknowledge the significant global burden posed by paediatric ocular surface health issues. Based on a median prevalence rate of 23.7% observed in school and community studies, an estimated 495 million children worldwide are affected by ocular surface disorders.

In line with the expected outcomes of observational epidemiological studies, the studies included in the analysis exhibited a high degree of heterogeneity. The wide variation in DED prevalence estimates reflects significant clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies, including choice of clinical versus community or school-based cohorts. The studies included in our metaanalysis differed in population characteristics, study designs, general climate information and definitions of DED, all of which add to the uncertainty in overall prevalence estimates.

The prevalence of DED in our meta-analysis differed significantly between studies using clinical diagnosis versus questionnaire, 16.6% and 34.6%, respectively. Vehof et al’s study in adults found that dissociation of signs and symptoms of DED is an indicator of self-perceived health.69 This finding suggests the possibility of a similar pattern existing among children. Higher prevalence of DED based on symptom-focused questionnaires in children is associated with more corneal nerve fibres and lower pain tolerance. Spierer et al showed that mechanical thresholds and pain thresholds correlate with age, resulting in children’s susceptibility to detecting ocular surface discomfort.70 Conversely, clinical test thresholds designed for adults may not be directly applicable to children. Healthy children typically exhibit a thinner lipid layer compared with adults.71

Additionally, asymptomatic children may present with alterations in the appearance and function of their meibomian glands.72

The OSDI questionnaire, comprising 12 questions, includes inquiries such as whether vision problems have impacted nighttime driving (question 7) or computer usage or bank machine (question 8), which may pose challenges for children to answer. Chidi-Egboka et al found that 57% of children required adult supervision to complete the OSDI questionnaire, possibly due to difficulty understanding certain symptoms. This highlights children’s lesser awareness of DED-related issues and terminology compared with adults.64 Modifications to questionnaires, such as annotations or adjusted wording, may mitigate bias. Given the varying cognitive abilities of children, the questionnaire should include different versions for different age groups (0–4 years, 5–11 years and 12–17 years), with a parental proxy option for younger children who may have difficulty expressing symptoms.73 For younger children (5–11 years) whose language skills are still developing, a simplified verbal and 3-point response scale with an expression scale ranging from happy to sad is used to help children understand the questions more easily.74 Hence, tailored diagnostic tools and further research are necessary for paediatric DED diagnosis.

We found that the prevalence of DED was 18.7% before and 44.1% after the COVID-19 outbreak (p=0.01 for subgroup heterogeneity). Globally, governments implemented various control measures, such as restrictions on public activities, home quarantine, social distancing and school closures. Online schooling was used as an alternative to face-to-face teaching.75 In line with other studies, Saldanha et al found an increase in the prevalence and severity of DED in adults following the COVID-19 outbreak.76 Of the eight studies included in the analysis that were conducted after the COVID-19 outbreak, four studies46 53 61 62 reported a high prevalence of DED. Three46 53 61 used the OSDI questionnaire and one62 used the DEQ-5 questionnaire. These studies involved high school students, potentially facilitating questionnaire comprehension. Conversely, the prevalence rates in the other four studies54 58–60 closely aligned with the pre-COVID-19 average of 23.7%. The relationship between COVID-19 and DED may be influenced by various factors, necessitating further research to understand its effects on paediatric DED.

Contact lenses are recognised as an independent risk factor for DED in adults, but their impact on children remains inadequately characterised. Among the 11 included studies, only 3 used both signs and symptoms for diagnosis. Notably, two studies reported prevalence rates of less than 10%, while the prevalence of DED diagnosed using symptoms varied considerably. The relationship between DED and contact lens wear in children lacks definitive evidence. Given the rising prevalence of myopia and the increasing use of contact lenses to manage it among children, comprehensive multicentre studies are warranted to elucidate the association between DED and different types of contact lens use in this population.

This study reveals potential associations between climate factors and the prevalence of paediatric DED through a metaregression analysis incorporating general climate information. We found increasing rates of DED with greater temperature and closer distance to the equator. Higher latitude results in a smaller angle of direct sunlight exposure, resulting in a lower impact on the ocular surface, likely yielding a lower prevalence rate.77 Although the prevalence of DED increased with increasing temperature in our study, consistent results have not been obtained in several studies, and the relationship between temperature and DED requires further study.78

79 Using more detailed environmental factors in a climate model (subtropical monsoon vs Mediterranean climate, etc), we may be able to better simulate the local effects of environment.10

This study highlights the urgent need to prioritise paediatric ocular surface health as a distinct clinical and public health concern. Traditionally underestimated, DED in children presents unique challenges, including the absence of standardised diagnostic criteria, which contributes to inconsistent prevalence estimates and hinders effective management. The paediatric ocular surface is anatomically and physiologically distinct from that of adults, rendering it more susceptible to environmental and behavioural influences such as increased screen time, contact lens use and extreme climates.

To improve detection and treatment, tailored diagnostic tools—such as simplified questionnaires and pediatricspecific clinical tests—are crucial. Clinicians must also account for environmental and lifestyle factors when evaluating children for DED, with a particular focus on high-risk groups. Future research should prioritise developing standardised diagnostic criteria and age-appropriate assessment tools for paediatric DED. Largescale, multicentre studies are needed to investigate regional and environmental influences on prevalence and to clarify associations with emerging risk factors like digital device usage and climate. Longitudinal studies are also warranted to explore the long-term effects of paediatric DED on vision, mental health and educational outcomes. Through improved awareness, prevention strategies and targeted interventions, the growing burden of DED in children can be effectively addressed, ensuring better outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Conclusions

This comprehensive metaanalysis demonstrates that DED is common in the paediatric population under the age of 18 years, which poses a serious burden to individuals and society. The prevalence and burden of DED are likely to increase due to the widespread use of electronic screens and lifestyle changes resulting from COVID-19, which may affect children’s mental health and educational attainment. Varying diagnostic criteria and inconsistencies in DED questionnaires for children have led to heterogeneity in its observed prevalence. The substantial variation in prevalence estimates reflects the need for standardised diagnostic criteria and age-appropriate diagnostic tools. Addressing paediatric DED will require a multidisciplinary approach that considers both clinical and environmental factors. Enhanced awareness and targeted interventions are critical for mitigating the growing burden of paediatric DED and safeguarding children’s ocular and overall health.

References available on request

Written by: Yuhao Zou1, Dongfeng Li1 2 , Virgili Gianni3 4, Nathan Congdon2 5 6 , Prabhath Piyasena2, S Grace Prakalapakorn7, Ruifan Zhang1, Zixiang Zhao1, Ving Fai Chan2 , Man Yu1

1Department of Ophthalmology, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences & Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China

2Center for Public Health, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, UK

3Department of NEUROFARBA, University of Florence, Firenze, Italy

4IRCCS – Fondazione Bietti, Roma, Italy

5Orbis International, New York, New York, USA

6Zhongshan Ophthalmic Centre, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

7Departments of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA Nathan Congdon

Read the full article HERE

Find more CPD HERE